At the end of 2025, at almost 50 years old, the Georges Pompidou National Center for Art and Culture temporarily closed its doors to undergo its first major renovation since opening: an open-heart operation accompanied by a facelift, scheduled to last until 2030.

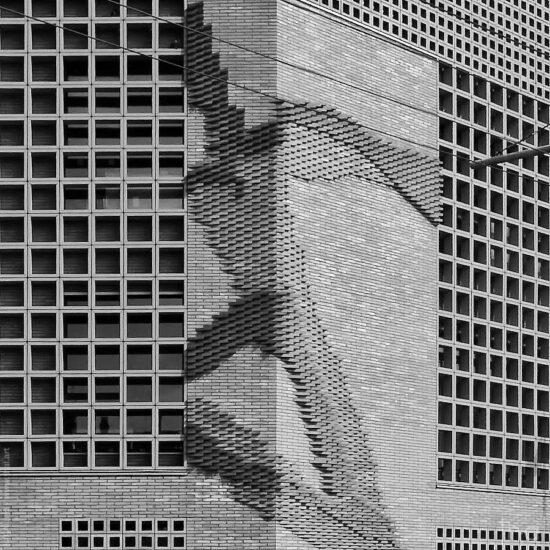

A disruptive UFO of modern architecture, Beaubourg (as it is known to its friends) is nevertheless far from being constructed like a human being, or even a classic building, as it displays its vital functions on the outside, including its famous transparent “digestive tract,” which visitors to the museum of modern art must pass through.

Its two designers, architects Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, emphasized the building’s technical and circulation functions, thereby radicalizing certain principles of Functionalism, the movement initiated by Walter Gropius (of the Bauhaus) and developed in the 20th century by figures such as Louis Sullivan, Adolf Loos, and Le Corbusier.

Color conceptualization and architecture

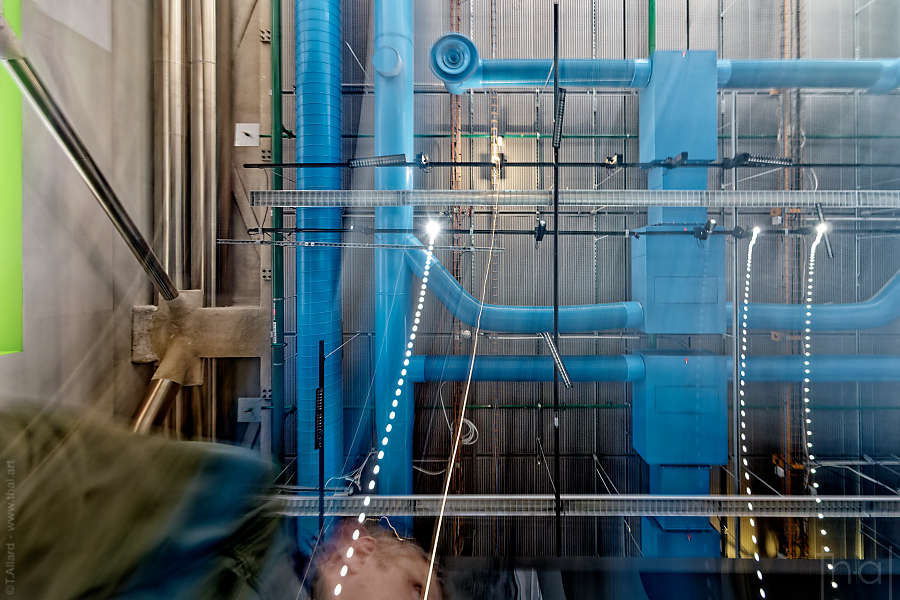

The ducts and circulation spaces of the Centre Pompidou, which are visible on the façade as well as inside, are coated in primary colors or white to indicate their function to visitors.

The architecture thus gives way to symbolic markers, conduits in coordinating colors.

Their externalization around the building effectively frees up space inside and makes the spaces highly modular.

When the Pompidou Center hosted an exhibition on Le Corbusier, it was an opportunity to recall that this architect also used color as a technical or architectural marker.

To cite an example consistent with Beaubourg: inside the Couvent de la Tourette, basic colors—blue, red, green, and yellow—accentuate the pipes, doors, furniture, and structural elements.

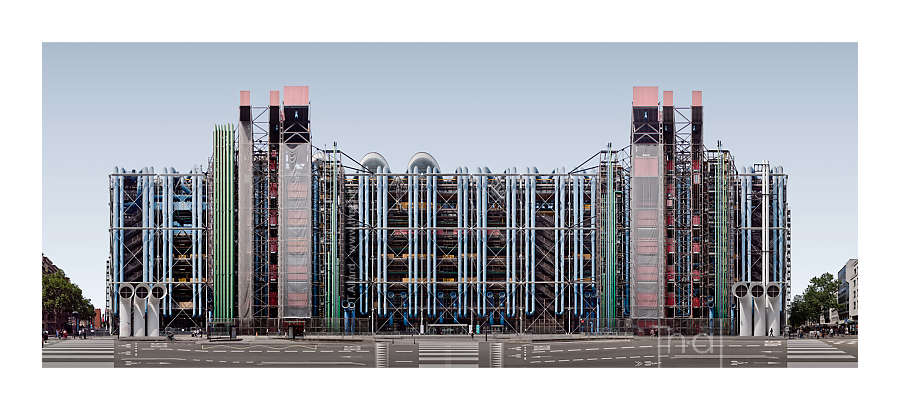

The most radical experimental and technical façade of the building is located at the rear and features vertical and horizontal ducts colored with the five shades from the Centre Pompidou color chart.

On Rue Beaubourg, a relatively narrow street congested with traffic that prevents visitors from seeing the building in its entirety, I created this panoramic view of the Centre Pompidou just before its 2025-2030 renovation began.

Beautiful, like Beaubourg?

This is the question that has been upsetting the entire world since the first day the worm tunnels of the building emerged from the ground.

This experimental architecture, which would not have looked out of place in an industrial setting, caused a scandal in 1977 (and continues to divide opinion), especially as it was located in the heart of Paris, a city dominated by the uniformity of Haussmannian architecture.

With its Meccano-style assembly, standing like a child’s toy amid “adult” buildings, this ugly duckling of 20th-century architecture remains a unique specimen in the world, rejecting the idea of beauty in architecture.

The circulatory color code of the Centre Pompidou

Particularly striking on the rear façade of the building, the color scheme of the Centre Pompidou is also found inside, mainly along the corridors and on the ceilings.

The color chart used by the architects at the Centre Pompidou includes five significant shades:

Red for public circulation and objects (escalators, elevators, and freight elevators).

Blue for air (air conditioning and ventilation). This is the most widely used color, particularly on the rear facade and on all ceilings.

Green, for water (sanitary facilities, air conditioning, and fire hydrants) identifies hydraulic pipes.

Le Yellow, ..

White for the external cooling towers on the roof and around the square (periscope-shaped tubes of various sizes) and, more generally, for the entire metal structure.

The Centre Pompidou or fluid mechanics

The main building, which houses a modern art museum, a library, exhibition galleries, and theater and cinema auditoriums, welcomes between 8,000 and 10,000 visitors per day, depending on the time of year.

It is one of the most visited art centers in Paris after the Louvre and the Gare d’Orsay, and one of the twenty most visited in the world.

The Centre Pompidou, which is designed to accommodate large numbers of visitors, favors an architecture of empty space.

Inside, freed in part from technical piping (except on the ceiling), large platforms can be filled and emptied throughout the day.

Outside, the two designers, Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers, chose to create a large empty space in the form of a square covering an area equivalent to that of the building, thus freeing it from the dense construction constraints of this Paris neighborhood.

Visitors arrive via a sloping public square, a veritable “spillway” that naturally draws them downwards to a second square located inside: the Forum. This huge reception hall acts as a distributor for the flow of people: on one side, those going directly to the library, and on the other, visitors to the museum of modern art (or temporary exhibitions), who are directed into the mandatory passageway formed by the external circulation tubes.

Human flow

The Piazza

The gentle artificial slope (11%), inspired by Italian squares, is enough to encourage many visitors to sit on the ground in front of the building. It also attracts street performers and other entertainers.

Learn more about the Piazza at the Centre Pompidou..

The Forum

The lobby of the Centre Pompidou is a vast central space covering an area of approximately 7,500 m² and accounting for 15% of the total floor space accessible to the public.

Its ceiling rises to a height of nearly 10 meters (compared to 7 m on the other floors) and, for those who look up, reveals all the exposed piping on the ceiling, as in the rest of the building.

On both sides of the forum, we find the color red, symbolic of the movement of people and objects on the sides of the escalators.

A mezzanine, which surrounds three sides of the forum, houses functional areas such as a children’s play area and fast food outlets. It provides access to the other floors of the building.

The Escalators tube

Nicknamed “the caterpillar,” the series of transparent tubes housing the escalators is the building’s symbolic architectural feature, running diagonally across the main façade and providing access to the main exhibition areas.

Humans, who are transported through pipes (like water, electricity, or air), contribute to the concept of the circulation of “vital” flows within the building.

The caterpillar ultimately serves as a vehicle for a vertical architectural journey at controlled speed, allowing visitors to observe the technical intricacies of the other tubes on the façade and gradually admire Paris.

The elevators

Framed in red, like freight elevators, elevators are accessible from the exterior walkways.

The walkways

The horizontal walkways are covered to varying degrees, depending on the floor, and all run along the main façade of the Centre Pompidou.

They are mainly connected to the entrances and exits of the exhibition areas and serve as emergency exits for the entire building.

The outdoor terraces

As the final stages of the museum tour, the building has always had three outdoor terraces on the fifth floor, offering spectacular views of Paris.

At both ends of the museum, each terrace features a few sculptures and a view of Montmartre on one side, or Notre Dame on the other.

A panoramic roof terrace was added later on the top floor restaurant level.

The circulation of knowledge

Art museum, exhibition galleries, and creative workshops

Next to a renowned National Museum of Modern Art and temporary exhibition galleries, creative workshops are open all year round to children and teenagers.

The Library

Free and open to the public, the Public Information Library (Bpi) is located inside the Centre Pompidou and spans three floors of the building.

Dedicated to public reading of encyclopedic works in all formats, but only on site (no home loans), the library plays a major role in the flow of visitors to the Centre Pompidou.

The circulation of flavors

Before the Pompidou Center’s renovation began in 2025, there were two dining areas in the building: one located in the Forum on the ground floor and the other on the top floor.

It is noteworthy that, having been designed by different architects, they felt the need to create a few “cells” to isolate customers somewhat amid the huge industrial-style open spaces.

The Café central

Located on the mezzanine above the forum, Café Central was designed by Spanish designer Jaime Hayon.

The space is organized around small pavilions with colored glass, which create areas of privacy.

The Georges restaurant

The gourmet restaurant located on the top floor of the Beaubourg Center dates back to the 2000s. Its design was entrusted to the architectural firm Jakob and MacFarlane.

With its terrace offering a panoramic view of the capital, the restaurant has become a highly sought-after Parisian rooftop spot.

The tubular ceiling framework remains in place throughout the restaurant area, although a few organically shaped alcoves have been added to create more intimate spaces.

The bold and controversial choice of French President Georges Pompidou, who died before the project was completed and gave his name to the “Beaubourg plateau” project, inaugurated a line of “builder” presidents.

His immediate successor, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, with La Cité de la Villette, and even more so François Mitterrand with the Grande Arche de la Défense, the Arab World Institute, and the BNF (which bears his name), continued this legacy.

Thierry Allard

French photographer, far and wide

You may also be interested in other examples of Parisian architecture

2025-2030: the Centre Pompidou regains its luster

The multiple interventions that require the Pompidou Center to be completely emptied of its furniture and occupants for five years include asbestos removal combined with energy optimization of the entire building, compliance with fire safety standards, replacement of elevators, and renovation of the air conditioning system and cooling towers.

As for its facelift, its colors will be revived after corrosion treatment and replacement of the bay windows.

The interior, particularly the Forum, is also undergoing a major reorganization by the Franco-Japanese duo Nicolas Moreau and Hiroko Kusunoki.

Outside, the square has been slightly modified by the Moreau Kusunoki agency in association with Frida Escobedo Studio, with the addition of stairs and steps on the sides.