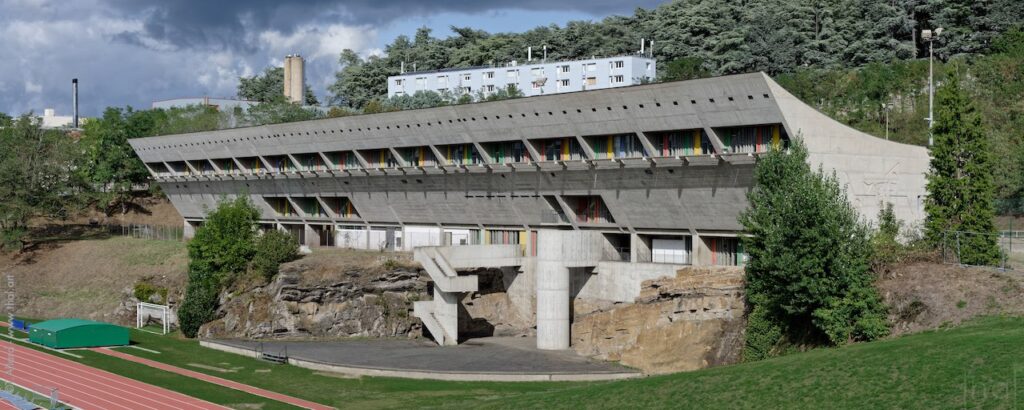

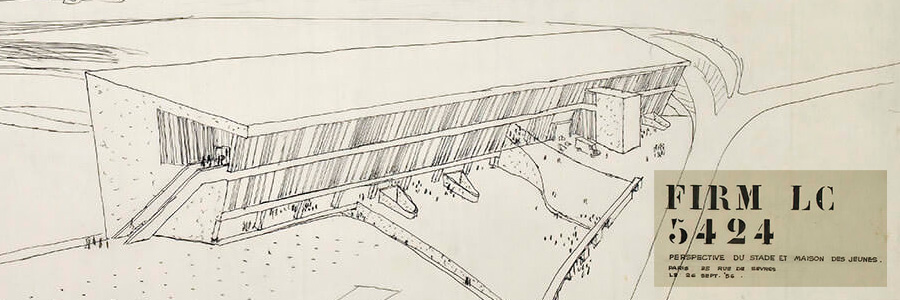

Le Corbusier’s cultural building projects its trapezoidal shape into the air like a sculpture, set firmly on a stone base.

Its sloping walls, curved roof and composition of windows and colored panels make the building unique, representing Le Corbusier’s final contribution to twentieth-century Brutalist architecture, as it was the last building of which the architect saw the shell completed during his lifetime.

The building, erected in 1965, is the only one of Le Corbusier’s architectural ensemble in Firminy to have been listed as a Unesco World Heritage Site in 2016.

For this multi-faceted building, Le Corbusier freed himself from a number of constraints, and his ” Maison de la Culture et de la Jeunesse” (House of Culture and Youth ) freed itself somewhat from the Modulor measurement system that the architect developed in the 1950s.

However, the building still respects a few points of the” new architecture “, with its free plan, pilings and facades without load-bearing walls.

The architect signs his creation with the symbol of an open hand and an artistic fresco on one of the gables.

A multicolored cultural space

Scattered in small touches, inside and out, the color covers all the building’s wooden doors and panels.

For Le Corbusier, yellow, red, blue and green represent “essential joys”.

They symbolize three fundamental points of the urban planning rules published by the architect in his Charte d’Athènes: sun, space and greenery.

These three elements are represented more figuratively on the facade of the Firminy housing unit.

The sloping facades of the Maison de la Culture in Firminy-Green

East facade

The east facade, slightly inclined at 8°, is visually segmented by 17 transverse reinforced concrete porticos, as well as by multiple glazed bands accompanied by narrow painted wooden panels, some of which are real shutters that can be opened to ventilate the building’s interior.

The 16 bays of the Maison de la Culture are punctuated by the famous “pans ondulatoires“, compositions of vertical windows inspired by those created for the Tourette convent with composer-architect Iannis Xenakis.

Main access to the second floor of the building is via external structures, either via the main access ramp leading to the central reception hall, or via two small, off-center emergency staircases, each resting on stilts.

Along the façade, 16 concrete benches with rounded tops echo the shape of the roof.

Le Corbusier frequently used ramps to enable visitors to appreciate his architecture, as in the architectural promenade at Villa Savoye.

On the north side, the first level of the building shows its structure on stilts.

The west facade

The 53° slope of the west facade follows the slope of the athletics stadium bleachers directly opposite.

For this Maison de la Culture, Le Corbusier was keen to integrate his architecture into its surroundings.

A small cliff, the remains of an old sandstone quarry preserved by the architect, serves as a promontory for his slender construction.

Compare this with Marcel Breuer’s spectacular cliff-top building in Flaine.

An exposed coal seam in the middle of the rock symbolically links the building to Firminy’s mining history.

Next to an external staircase, a cylindrical tower conceals a spiral staircase that allows actors to reach the stage of a “théâtre de verdure” (green theater).

The south gable, a formwork story

Le Corbusier often enjoyed adding his artistic touch to the surroundings, or directly to his buildings, as in the case of the nearby Firminy-vert housing estate.

However, the original plans for the Maison de la Culture did not include any frescoes, although a staircase and a few strips of glass were to decorate the side.

The vagaries of construction had turned this south gable into a blind façade, and although the lower part of the wall had already been poured, the mayor of Firminy, Claudius-Petit, asked Le Corbusier to add some recessed drawings to the wall.

The concreting work is suspended halfway up the wall, while the negative of a fresco is added to the upper formwork.

Once the formwork has been removed, other relief motifs will be added to the lower section, inverting light and shadow.

Le Corbusier’s fresco represents the major arts practiced in the Maison de la Culture: theater, painting, sculpture and music.

The interior of the Maison de la Culture Le Corbusier

The cultural space houses a library and several rooms, including an auditorium, a performance hall, art and body expression rooms, and exhibition halls.

The door handle at the main entrance, which leads to the second-floor lobby, is signed with a figure dear to Corbusier: the “open hand“.

He was not the only architect to use a hand as a signature, since at the same time Oscar Niemeyer incorporated a sculpture of his hand into the Volcan du Havre.

Like the living units, the second floor is criss-crossed by an “interior street”, a wide corridor dotted with colorful doors and ventilation shutters, which runs alongside the east-side bay windows.

The little fireplace

A central staircase connects the reception hall to the lower level, leading to a multi-purpose “petit foyer”.

Several narrow, colored doors lead to six dressing rooms for performers in the outdoor “théâtre de verdure”.

The ceramic-encrusted concrete table that acts as a railing under the staircase in the small foyer is the only furniture designed by Le Corbusier.

In the second, adjoining, more convivial room, the fireplace and furniture were designed by Parisian designer Pierre Guariche using measurements taken from the ” Modulor “, as for the other furniture in the building.

The grand foyer

The large foyer is transformed into an auditorium thanks to bleachers with folding seats designed by Pierre Gariche.

The audience enters from above, and large black curtains block out the light from the bay windows.

The showrooms

In the exhibition halls, as in the auditorium and auditorium, the bleachers rest on the self-supporting wall at an angle of 53°, a very significant and unusual angle for bleachers.

The ceilings, simply painted white to better diffuse the zenithal light, reveal the cables that directly support the roof slabs.

A roof suspended from Le Corbusier’s ideas

It might have seemed logical that a house of culture designed by Le Corbusier, which welcomes the public, could justify having a large terrace roof, but this time the architect abandoned his flat roof, and racked his brains to produce his latest architectural UFO.

The key to an inverted vault

The only one of its kind, the inverted-vault roof of Le Corbusier’s Maison de la Culture is supported by 132 18 m-long cables attached to concrete beams linking the transverse porticos.

On the front, small niches hold two nuts, allowing double cables to be tightened if necessary.

The cables originally supported a roof composed solely of waterproofed cellular concrete roof slabs less than 10 cm thick.

This specific construction feature, which gives the roof a certain flexibility by allowing it to move, has led to serious waterproofing problems over time.

While the cables were stretched so tightly as to transform the roof into a huge oak flue, water drainage was imperfect due to the only 2 gargoyles placed at the ends of the building, more than 100 meters apart.

The moving roof, with its extremely simple “water path”, was the Achilles’ heel of the structure, which could be further endangered in winter by snow accumulation.

Compare this with the more sophisticated waterway of Le Corbusier’s conical church, just a hundred meters away.

Renovated roof with overlays

In 50 years, the roof has undergone two major renovations to correct its waterproofing problems and add thermal insulation, which was not a key concern when the building was designed.

The most recent, dating from the 2010s, should enable us to make more lasting improvements to the roof.

Rainwater management has been redesigned, with the creation of a true oak flue running the entire length of the building, in the lower part of the roof, and the addition of five internal downspouts to complement the two existing gargoyles. Rainwater collected in this way is evacuated much more efficiently and no longer runs the risk of stagnating on part of the roof.

Insulation and, above all, waterproofing problems, which were threatening the building, have been corrected with layers of materials:

Cellular concrete slabs are covered with a vapour barrier and 12 cm of rock wool insulation, followed by a 4 cm thick hot-welded reinforced bitumen screed and, finally, a synthetic rubber membrane.

The cables, which are still in good condition, probably because they were indoors in the open air, can easily withstand these new, relatively light materials, which almost triple the thickness of the original roof!

This waterproofing upgrade is reminiscent of the one I reported for the Cnit vault in Paris.

Please respect the copyright and do not use any content from this article without first requesting it.

If you notice any errors or inaccuracies in this article, please let me know!

You may be interested in other reports on Le Corbusier architect: