The first 3 buildings of the Unesco headquarters in Paris were designed and built in the 1950s by a trio of architects, Marcel Breuer, Bernhard Zehrfuss et Luigi Nervi, under the supervision of an international committee of five illustrious colleagues, including Le Corbusier, Lucio Costa (Brasilia) and Walter Gropius (founder of the Bauhaus)..

This assembly of 8 renowned architects made it easier to impose uncompromising functionalist architecture on the member countries of the fledgling Unesco.

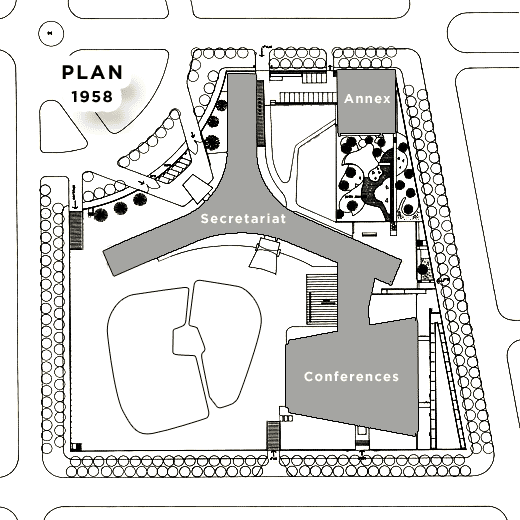

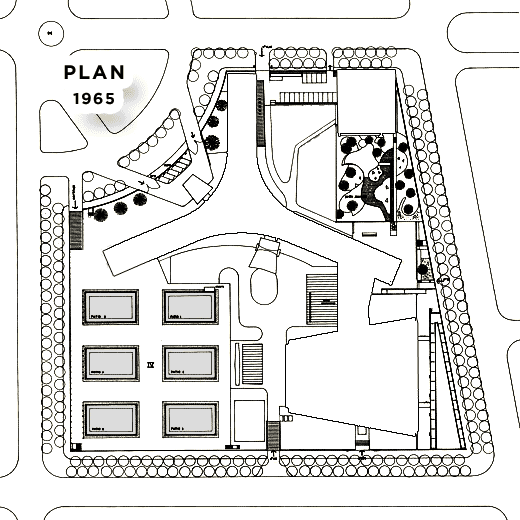

Among the 3 works built in 1958 on a 3-hectare former military site proposed by France, two of them, linked by a salle des pas perdus, were to become emblematic of twentieth-century Brutalist architecture.

A trapezoidal building accompanied by a 7-storey, three-pointed star-shaped structure on stilts was the focal point for all these architects, eminent specialists in concrete.

Unesco Conference Building

Load-bearing trapezoids

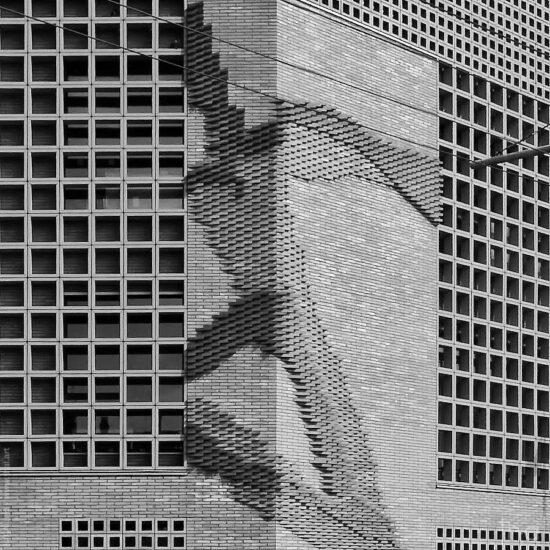

A veritable icon of Brutalism in France, with its accordion-bellows look and 3,000 tonnes of concrete, the Pavillon des Conférences also stands out for its large, blind, trapezoidal facades, the relief motif that animates them and the roof (seen from the air).

Its formal features, such as the hollow molding of the concrete, reveal the influence of Marcel Breuer on this building.

The deep groove effect, created in concrete veil, increases the strength of the 2 inclined load-bearing walls that support the ends of the roof, while giving them a certain thinness (35 cm thick).

The recesses also act as “sound traps” to enhance the interior acoustics of the conference rooms.

On either side of the building, free-standing (non-load-bearing) facades allow glazed sections to be integrated freely with other wall sections clad in travertine facing stone from Italy.

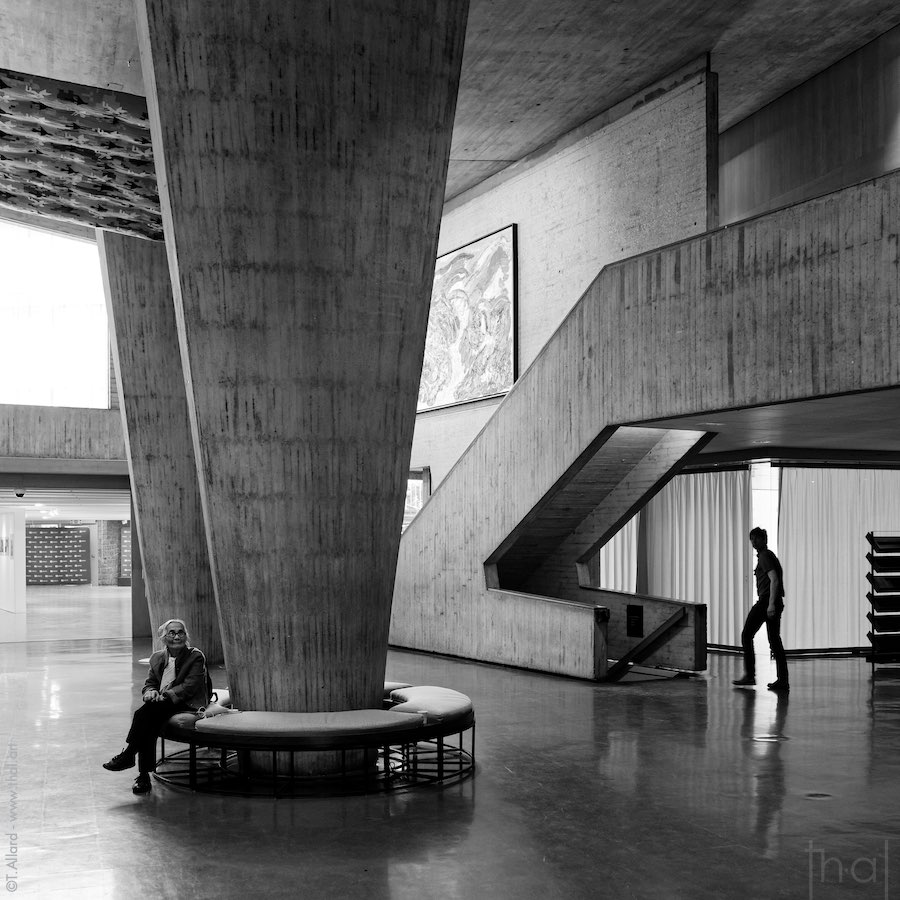

Central entrance hall

The concrete roof, clad in copper on the outside, features 2 inverted slopes that meet above a large hall in the center of the building.

It is supported by a row of imposing, rough-cut pillars.

These 6 pillars have the particularity of having an oval cross-section at their base and ending in a very elongated rectangular cross-section, which, in profile, also gives them a trapezoidal shape.

The technique for switching from one shape to another is fairly straightforward, since it involves creating, as in a simplified 3D view, a flat section starting from the bottom of the column and widening over the height.

Grand auditorium

The pavilion houses several meeting rooms and 2 conference rooms, which feature the reverse side of the raw concrete “accordion” at the back of the stage and on the ceiling.

Points of convergence in this blog:

- The “square to round” architecture of the Firminy church.

- Le Corbusier’s trapezoidal Maison de la Culture.

- The raw concrete vaults of Bernard Zehrfuss’s Cnit or Henri Pottier’s auditorium in Lyon.

- The variety of concrete formwork in Oscar Niemeyer’s PCF headquarters.

- In search of fluted concrete in Bordeaux.

Unesco Headquarters Secretariat

Born under an auspicious star

Shaped like a Y, the Unesco secretariat’s height was limited to 31 meters, and its branches were rounded to respect the layout of the Place Fontenoy, which is in line with the Champ de Mars, the Eiffel Tower and the Palais de Chaillot.

Transparent architecture, raised 5 metres above the ground by 72 concrete pillars lined up in double rows, the building displays its raw materials without embellishment: concrete, glass and steel, as well as paving and facing stones and wood furniture from several Unesco member countries.

On the south side, the glazed strips overlooking the “Piazza” are protected by brise-soleil slats topped with tinted glass that filters out infra-red rays, while allowing ultra-violet rays to pass through.

Vertical travertine panels are arranged in an alternating pattern on every other storey, giving rhythm to the façade.

Bernard Zehrfuss, as the project’s chief architect, supervised this building in particular, although the other 2 architects also made significant contributions.

The massive concrete canopy, which resembles a “religious cornice”, benefits, like the pillars of the buildings, from the expertise of Luigi Nervi, who, as well as being an architect, was above all an engineer.

On the east side, the facade is very similar, but the glass filters (less essential in the morning) have been removed and the canopy replaced by a central emergency staircase in precast concrete.

The fire escape illustrates the functionalism that prevails in all buildings:

Composed of 151 steps weighing 65 kg, each step can support up to three people.

The central column conceals a water column, and each floor has a connection for a fire hose.

On the west side, Unesco’s Fontenoy façade (right) does not protrude at all, to blend in with the other buildings overlooking the square.

At the eastern end, an outdoor terrace, partly covered by the second floor of the secretariat, forms the meeting point between the main buildings, allowing visitors to appreciate the components of the various Brutalist architectural styles.

On the exterior, travertine is the main stone “chosen” to break the monotony of concrete. It decorates the first three Unesco buildings, intermittently cladding the facades, and even more so, the 3 gables of the secretariat.

Travertine from Tivoli, Italy, is a natural stone appreciated for its beauty and durability. It was used extensively in ancient Roman architecture and continues to be prized in contemporary architectural projects for its texture.

Secretariat first floor

Thanks to its Y shape, the Unesco secretariat has a central focal point that concentrates the technical parts and regulates (or brings together) the thousand or so people who may occupy the building.

The economy of materials, which defines the architecture of the first three buildings, determines the shape and aesthetics of the pillars according to the load they support.

Spaced 6 meters apart at their base, these pillars have a function other than that of supporting the structure, as they can be crossed by a water drainage pipe.

Points of convergence in this blog:

- Variety of formwork and exposed stone, Marcel Breuer’s Brutalist style for the Flaine ski resort.

- Le Corbusier’s 5 points of new architecture.

Delegation pavilion

A cube at the bottom of the garden

The Delegations and Non-Governmental Organizations Pavilion, which stands slightly apart and has no covered connection with the other two buildings, is located at the end of a Japanese garden, originally created by sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

The small, square building overlooks the “Peace Garden” and its two chosubachi (ancient-style ponds).

It features the same glass elements as the secretariat, with travertine facades, and rests on its own trapezoidal pillars.

The garden adds 80 tonnes of stone and numerous trees, donated and shipped from Japan, to help meditate within the Unesco enclosure.

From Unesco House to Unesco Palace

Originally named “Maison de l’Unesco”, the architectural complex is also known as the “Palais“, perhaps because of the extensions that were added after its construction.

Bernard Zehrfuss’s underground extension

Just 5 years after Unesco moved in, the number of member states had increased by a third, and the 3 original buildings were no longer sufficient to accommodate all the delegations.

A new call for tenders was made to the 3 architects, who proposed the erection of a new 15-storey building, rejected by the Paris Sites Commission.

Bernard Zehrfuss, who was left alone to submit a new project, drew his inspiration from semi-underground villas visited in the Roman city of Bulla Regia, Tunisia, to propose an architecture buried beneath the main square.

Surrounded by six patios providing light and silence, two floors of offices are buried in the basement, eliminating an outdoor parking lot and restoring part of the central square without overshadowing (literally and figuratively) the two original iconic buildings.

Large hedges surround the patios to ensure privacy for the courtyards.

Bernard Zehrfuss constructed two other buildings for Unesco in the 1960s-1970s in the same district: the Miollis annex (Unesco V) and the Bonvin annex (Unesco VI). On this subject, see the article (in French) from la façade au carré.

Points of convergence in this blog:

Tadao Andō’s Zen extension

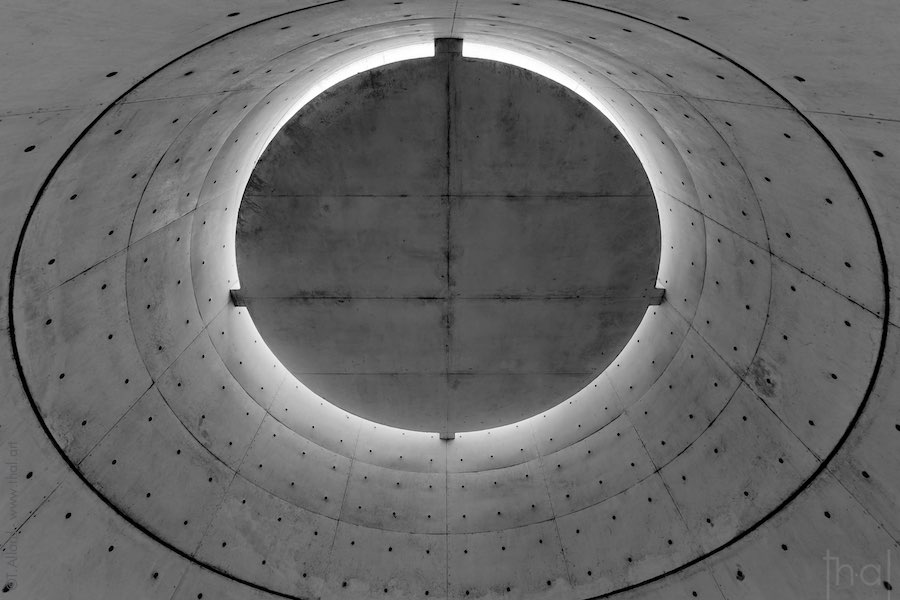

In 1995, Japanese architect Tadao Andō was authorized to add a 5th small concrete structure to the Unesco headquarters.

His “Peace Memorial” commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

This meditation space takes the form of a cylinder in rough concrete marked with perforations. It measures around 9 m high by 6 m in diameter, and its granite floor was taken from the rubble of Hiroshima.

With this latest construction, the Place de Fontenoy Unesco site appears definitively complete, and will probably see no further construction.

Artists’ meeting point in the Maison de l’Unesco

As soon as the building was constructed, an “Architecture and Art Committee” was set up to select the first international artists who would have the privilege of proposing works in specific locations.

Many other works of art were subsequently added to the collection.

Among the works installed in the Maison de l’Unesco, which you can see in some of the photos in this article, are sculptures by Henry Moore (above), Alexander Calder (in front of the secretariat awning), Alberto Giacometti’s “Walking Man” (inside the secretariat), a fresco by Jean Bazaine (under the delegations pavilion) and a fresco by Picasso…

Brutalist heritage and Unesco

Although the entire Unesco House is not a World Heritage site, we can be sure that it will be preserved by the international organization, which has the means to do so.

After 40 years of loyal service, a major program of works was carried out in the 2000s to completely restore the administrative buildings and underground courtyards.

Facades, glazing, sunshades, waterproofing of terraces and complete refurbishment of interiors and technical networks have given these buildings a new lease of life.

A new entrance was also created on avenue de Suffren, giving direct access to the conference building from the outside.

UNESCO headquarters can be visited intermittently, on Heritage Days or guided tours.

Brutalist architecture in France, a Unesco World Heritage Site

- Le Corbusier :

- The La Roche et Jeanneret houses

- The Cité Frugès

- Villa Savoye and gardener’s lodge

- Rental building at Porte Molitor

- The Cité Radieuse housing complex in Marseille

- Notre-Dame-du-Haut Chapel in Ronchamp

- Sainte-Marie-de-la-Tourette Convent

- The Maison de la Culture of Firminy

- La Manufacture in Saint-Dié

- Le Corbusier’s cabin in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin

- Le Havre by Auguste Perret

Thierry Allard

French photographer, far and wide

Please respect the copyright and do not use any content from this article without first requesting it.

If you notice any errors or inaccuracies in this article, please let me know!