In 1945, Le Corbusier developed his own unit of measurement, the Modulor, aimed at reintroducing the notion of corporality into architecture.

Using a skilful combination of measurements based on a human figure stretching its arm in the air, he defines the size of his buildings and their interior spaces, including furniture.

But this idea of a “standard man” whose use as a universal template would generate well-being, by replacing the “dehumanized” metric system, will not redefine the standards governing construction.

The master standard

The Modulor, a contraction of “module” and “nombre d’or” (golden number), is justified in terms of its dimensions by the division of its height of 6 ft (1.83 m) by the height of its navel at 3.7 ft (1.13 m) (equivalent to the distance between the top of the outstretched hand and the navel), which gives the golden number (1.619 m).

Other subdivisions are calculated from the mathematical Fibonacci sequence.

Modulor or fada-ometer?

More than a century after the advent of the metre as a universal measure, the idea of using a man’s silhouette as a measuring tool could question common sense.

In 1950, for anyone unfamiliar with Le Corbusier, he might have seemed like an eccentric, as some Marseillais thought, having nicknamed the “Cité Radieuse”, the first housing unit to use the Modulor, for various reasons, the “Maison du fada” (local slang for “madman’s house”).

At the time, the architect could easily be laughed at (in France) when he declared that the height of his 1.83 meters tall man corresponded to the six-foot height of well-built English policemen!

Despite this seemingly fanciful explanation, the Modulor was the result of Le Corbusier’s deep-seated desire to reintroduce human measurements into construction, while referring to the inches and feet widely used in the Anglo-Saxon world.

To make his concept appear as sensible as possible, he had drawn inspiration from illustrious predecessors by taking the trouble to develop a mathematical justification involving the golden ratio in his human construction.

Modulor basics

The Modulor’s 3 main dimensions – its height from head to toe, the distance from its outstretched arm to its feet, and the distance between its navel (placed at the center of the silhouette) and one of its extremities – are used to determine the size of interior spaces, or even bay windows.

Intermediate measurements derived from Modulor subdivisions are used to set furniture sizes and various thicknesses (or depths) for fittings and structures.

For example, the height of a table top was 27.6 inches (70 cm), that of a kitchen unit 33.9 inches (86 cm), a chair seat 16,9 inches (43 cm) and a bar top 4.5 inches (113 cm).

Measures that fall short of today’s Western standards.

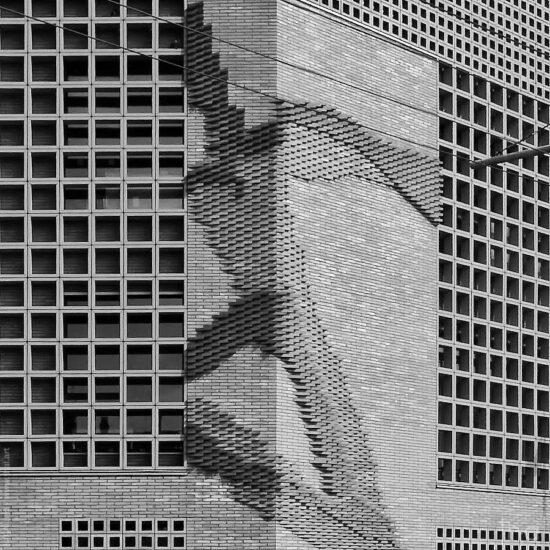

Le Corbusier gave himself the freedom to play with the Modulor silhouette, using it artistically in paintings and sculptures, and integrating stylized, recessed versions into concrete facades.

Transformed into an ink pad, the Modulor could also be integrated directly into scale drawings.

If you use your Modulor to measure a child’s bedroom in one of Le Corbusier’s housing units, or that of a monk at the La Tourette monastery, it measures:

- A Modulor arm raised: 7.4 feet (2.26 meters) high.

- A head-to-toe Modulor: 6 feet (1.83 metres) wide.

- Two Modulors from head to toe + one Modulor with outstretched arm: 19.4 feet (5.92 metres) in length.

At the ego game, the master takes six feet

The Modulor was originally intended to measure Le Corbusier’s height, 5,74 ft (1.75 m), as was the Oktameter reference model mentioned later in this article, before finally settling on 1.829 meters to adjust it to the round figure of 6 feet.

Did Le Corbusier think he was revolutionizing architecture by redefining the size of buildings and living spaces with a few measurements artificially linked to a template man he himself had decreed?

According to him, a home created using Modulor dimensions would provide its inhabitants with a sense of well-being and comfort.

He also believed that “mediocre” architects could create quality architecture using his Modulor!

Despite his genuine desire to build a humanized architecture with more organic references, his necessarily arbitrary unit of measurement could also appear as a form of dictate, that of an architect wanting to shape the world to his own hand.

In the end, this new standard of measurement proved to be as devoid of true universality as the palm, the cubit, the empan, or the other “random” human-based measures of feet or inches…

Sorry, for Anglo-Saxon readers 😉

Modulor in Le Corbusier’s French architecture

Between theory and practice, the Modulor quickly proved to be restrictive and limited in its application, and architects freed themselves from it to a greater or lesser extent, depending on the building.

In residential units

Modulor reigns supreme in the 4 French housing units (the 5th, located in Berlin, stands out for its 2.50 m ceiling height, in line with German standards).

At the bottom of each facade, stylized representations recessed into the concrete are there to remind us of the importance of the “bonhomme”.

The first housing unit, Marseille’s “Cité radieuse”, was built entirely using 15 measurements taken from the Modulor.

Modulor was also used, during Le Corbusier’s lifetime, for the Reze housing unit in 1955 and the Briey housing unit in 1960.

After his death, the Firminy-Vert housing unit was completed in 1967 by his disciple André Wogenscky.

In places of worship

The Chapelle Notre-Dame du Haut in Ronchamp (1955) and the Convent of Sainte-Marie de La Tourette (1960) were built during Le Corbusier’s lifetime using Modulor.

In the case of the Saint-Pierre de Firminy-vert church built by José Oubrerie after Le Corbusier’s death, there are a few (poorly documented) references to the Modulor, such as the size of the concrete slabs laid on the church roof.

In single-family homes

The Jaoul houses

The Jaoul houses are two villas built in 1953 in Neuilly-sur-Seine, near Paris. They are a concrete application of the Modulor principle: the size of the 12′ x 7.4′ (3.66 x 2.26 m) bay windows, the ceiling height of the second floor and the base of the Catalan vaults on the second floor bear witness to this.

The Cap-Martin shed

This is the ultimate culmination of Le Corbusier’s research into the notion of the minimum cell, which he had already experimented with in the 1920s for the gardener’s lodge at the Villa Savoye.

The cabanon, located near Monaco, was Le Corbusier’s favorite vacation spot at the end of his life (he died of a heart attack while swimming in the sea).

The Cabanon de Roquebrune-Cap-Martin is a 49.2-foot (15m2) square that is the width of 2 Modulors without the arm and the height of a Modulor with the arm extended. It comprises a single room for 3 functions: sleeping, washing and working.

Other buildings constructed in France using Modulor

- The Swiss Pavilion at the Cité Universitaire Internationale in Paris.

- The Manufacture de Saint-Dié, France, a prototype factory.

The Modulor, and after?

Despite the influence Le Corbusier had on many architects, particularly those he had trained, and the two books he published on the subject, the use of the Modulor did not survive very long after the death of its creator.

Some of Le Corbusier’s disciples, such as his pupil André Wogenscky, perpetuated the use of the Master’s standard in their buildings, as for the Firminy swimming pool, which will complete Le Corbusier’s largest architectural project in Europe.

After Le Corbusier’s death, Parisian designer Pierre Guariche designed the furniture for the Maison de la Culture in Firminy, based on measurements taken from the Modulor (see image illustrating this article).

Modulor, and before?

Le Corbusier didn’t invent anything with his template man. In fact, he drew inspiration from illustrious predecessors, most famously Vitruvian Man.

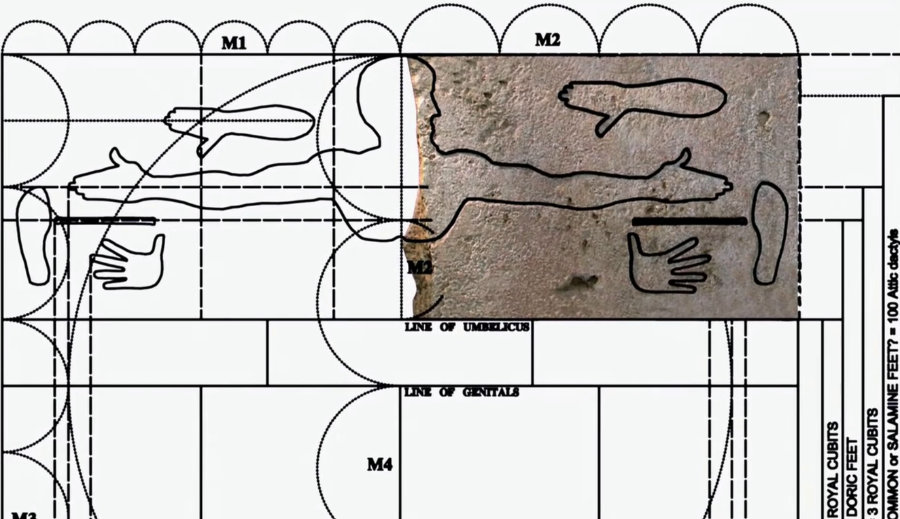

The Stone of Salamis

The Stone of Salamis, found in Piraeus, Greece, aligns and equates a series of units—hand, span, foot, fathom—that explicitly make the human body the common reference point for measurements used in classical Greek architecture.

It reveals, for the first time, a foot measuring approximately 307 mm (close to the modern Anglo-Saxon unit of measurement) alongside the Doric foot measuring approximately 327 mm and the Ionic foot measuring approximately 340 mm.

Vitruvius’ theory

Vitruvius was a Roman architect of the 1st century BC and author of the treatise “De architectura.”

In it, he theorized an ideal system of measurement used in the construction of buildings, composed of units related to parts of the body, such as the elbow, foot, palm, and finger.

He describes a man of ideal proportions standing in a circle with his arms and legs spread apart, with his navel serving as the center of gravity, making the human body a model of proportion for architecture.

Standing with his legs together in a square, his wingspan is equal to his height.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man

During the artistic, scientific and philosophical flourishing of the Renaissance, man was considered the center of the universe.

Around 1490, Leonardo da Vinci took up his pen and drew what would become the most famous representation of Vitruvian Man.

The Oktameter model

In 1936 (20 years before the Modulor), German Bauhaus architect Ernst Neufert, an admirer of Le Corbusier, developed a system linked to the golden ratio, based on a 1.75 m male standard (5,74 ft), with the aim of standardizing construction by normalizing interior spaces and everything that goes with them, such as furniture sizes, staircase step heights and so on.

The resulting octametric measurement system became a standard for Nazi buildings…

His comprehensive treatise on “The Elements of Building Projects” is still published today and is still a reference for many architects. His 2.50-meter (8,2 ft) grid has remained a standard for industrial building construction.

In the shadow of the Modulor

With its simplified male silhouette, artistically represented with talent by Le Corbusier, the Modulor could have contributed to perpetuating a form of patriarchal domination that had always been present in the world of architecture.

The choice of an “ideal” male body as a reference point, whatever its mathematical or philosophical justification, also echoed part of the fascist ideology to which Le Corbusier proved close.

This old-fashioned vision of standardizing and freezing a masculine representation seems disconnected from the evolution of man and the diversity that constitutes it. It’s probably not the architect’s best idea, even if it does arouse interest and become part of his legend.

A single meter, artificial but universal

Conceived during the Italian Renaissance from a formula linked to the oscillation of a pendulum, the “metro cattolico”, meaning “universal measure”, was scientifically defined in France after the Revolution of 1789.

The metre corresponded to 1/10,000,000 part of the distance from the North Pole to the Equator, measured on the Paris meridian.

The first platinum standard meter is kept in Paris under the name “Mètre des Archives”.

A century later, in 1889, thirty platinum copies were manufactured and distributed worldwide.

The problem with measuring standards is that, whatever the material they’re made of, they can expand or contract slightly according to temperature or humidity.

This is one of the reasons why, in the twentieth century, the measurement of the standard meter was dematerialized once and for all, and calculated on the basis of the speed of light.

Find out more about the history of the metre.

Thierry Allard

French photographer, far and wide

Please respect the copyright and do not use any content from this article without first requesting it.

If you notice any errors or inaccuracies in this article, please let me know!

You may be interested in other reports on Le Corbusier architect:

One thought on “ Modulor, Le Corbusier’s navel of the world ”

Comments are closed.