Built in 1989, the Grande Arche has established itself, thanks to its simplicity, as an architectural landmark in the heart of the La Défense business district.

Its architect, Johan Otto von Spreckelsen, turned out to be a shooting star, leaving the project soon after construction started and ascending a bit too quickly to the heavens he invited into his creation—never able to witness its completion.

Yet everything had started well for him, winning the international “Tête Défense” competition, launched in 1982 under the presidency of François Mitterrand.

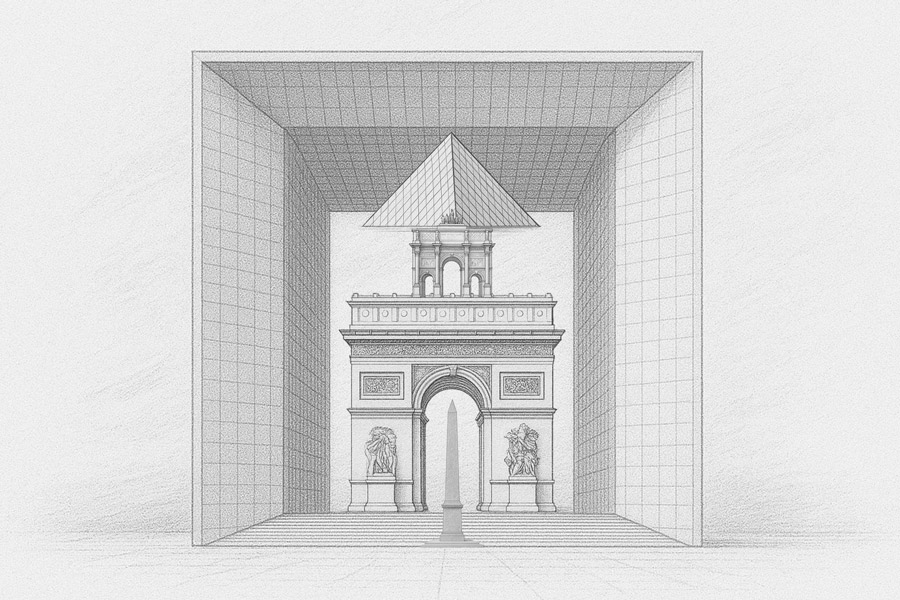

The aim of the competition was to design an original architectural structure, with no height restrictions, that would provide a magnificent conclusion to the historic Parisian axis linking the Louvre, the Champs-Élysées, and the Arc de Triomphe on Place Charles-de-Gaulle.

Architecture of emptiness, a cube pierced by genius

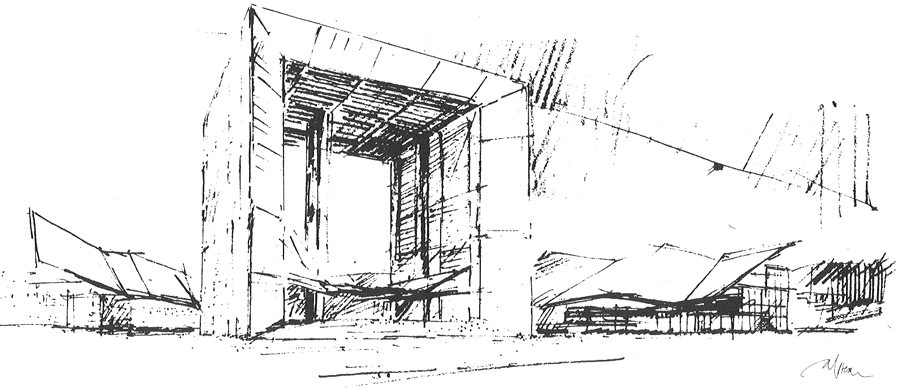

Faced with 423 other projects from around the world, an unknown Danish architect, working with an engineer, proposed a sketch of a simple hollow cube that leaves plenty of space for emptiness.

Rather than closing off the perspective of Paris’s historic axis, it extends it thanks to a giant 110-meter-square frame placed on the ground, transforming part of the sky into a 90-meter-high by 70-meter-wide canvas.

Johan Otto von Spreckelsen’s design was selected anonymously from among four finalist architectural firms, then chosen by the French president.

This perfectionist architecture professor, who at the time had only four small churches to his credit, quickly realized that for a monument of this scale, what was simple to design could prove extremely complicated to build.

The inherent difficulties of the construction site, combined with the troubled and shifting waters of the project, made him abandon it just one year after construction began.

Shortly thereafter, Spreckelsen learned that he was seriously ill and died prematurely, three years before the building was completed.

In the shadow of the creator

The experienced French architect Paul Andreu, who had been providing technical assistance to Spreckelsen since the beginning of the project, naturally took over and saw the project through to completion, staying as faithful as possible to the ideas of its creator.

Just as architect José Oubrerie should be credited for the church in Firminy that he designed in place of Le Corbusier, Paul Andrieu should always be associated with the Grande Arche, given how much he contributed to it.

The Quadrature of the Arch

The hypercube

Very soon after reading the competition brief, the Danish architect came up with the idea of creating a cubic building, an architectural form he was fond of.

A preparatory trip to La Défense allowed him to confirm his idea of a hypercube.

This would not detract from the backdrop* of the Arc de Triomphe, as seen from the Champs-Élysées.

*A test will be carried out later at the planned location of Tête Défense, using a plate raised 100 meters high by a giant crane, to validate the height of the Arch.

In hindsight, it is interesting to note that in 1989, just three months apart, two very simple architectural forms, a cube and a pyramid (the latter designed by architect Ieoh Ming Pei for the Louvre), were quite naturally inserted at either end of Paris’ famous historic axis.

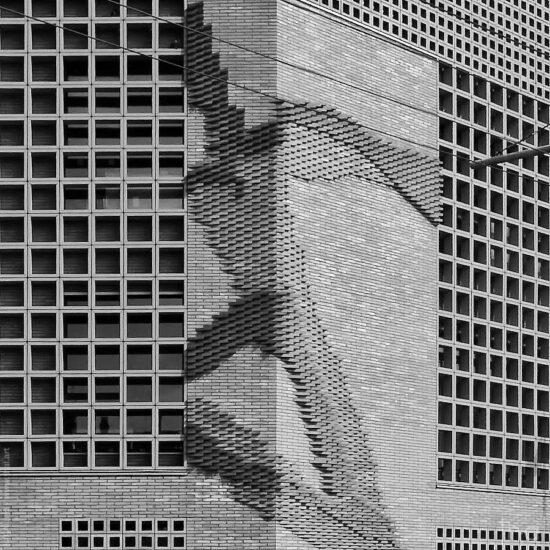

Just like some Egyptian pyramids were originally, the beveled edges of the large Arch are immaculate white, but instead of using limestone, Spreckelsen chose to use white Italian Carrara marble.

As this cladding was unable to withstand Parisian pollution, it was completely replaced between 2014 and 2017 with Bethel White granite, sourced mainly from American quarries in Vermont.

A massive and off-center mega sculpture

The entire “frame” of the Ark, including its base, weighs approximately 300,000 tons.

Made of stone, glass, and concrete (60% of which is high-performance), it appears to be “resting” on the ground, without actually being attached to the 12 piles 30 meters deep that form its foundations.

The underground infrastructure already present at Tête Défense (two highways and three railway lines) meant that the Arch had to be rotated slightly, at an angle of 6.3° relative to the alignment of the towers lining the Esplanade de la Défense, so that the right side of the building is always visible when viewed from the historic axis.

Note: this angle happened to be adjusted and inverted on the one opposite, which already shifts from the same axis, the Louvre and its pyramid!

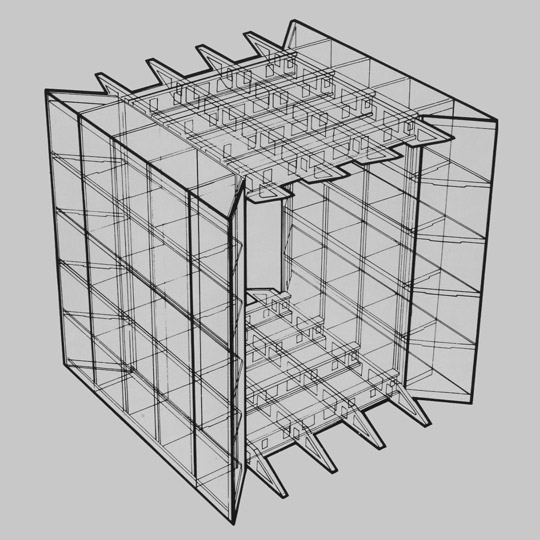

The dissected cube

The Grande Arche could be summarized as two buildings facing each other, connected at the top and bottom, with gables consisting of four solid sections and a large void.

But these four elements form a whole, making this a unique work of art with a blind façade pierced by a monumental opening!

The base and the forecourt

The thick line that closes the frame of the Ark at ground level is composed of monumental staircases on both sides.

The central opening of the Arche de la Défense, with its bevelled sides, creates a Venturi effect that causes the wind speed to increase.

Glass walls on the forecourt and a Teflon “cloud*” slightly mitigate this effect at ground level.

*The architect had instead envisioned “crystalline clouds” in his design. These were suspended glass structures, but they could not be technically realized.

Five transparent outdoor elevators depart from the forecourt and travel the entire height of the Arch to the upper level. However, these elevators have proven to be unreliable and are now rarely used.

The vertical studs

The hollow facades of the Arch are bordered vertically by 19-meter-wide bevelled blind walls.

The two vertical uprights contain, besides offices, the invisible skeleton of the building that supports the upper platform.

Spreckelsen would have liked to build it entirely by himself first, to make it exist as a temporary sculpture, but the usual rules of construction meant that the building logically rose in layers, from the bottom to the top.

The two facing interior walls reveal glazed boxes recessed within them, but the architect originally wanted these to be completely covered with square panes of glass, offering a smooth appearance like the exterior façades.

The upper platform

The upper platform, weighing 30,000 tonnes and spanning a free length of 70 meters, constitutes, along with the supporting skeleton, one of the building’s major technical achievements. Its framework consists of four mega prestressed reinforced concrete beams, each over 100 meters long and 9 meters high, which are reinforced, like a bridge, by tensioned steel cables.

The sloping blind facade on the Paris side conceals a staircase running almost its entire length, leading to a belvedere that allows natural light to flood the entire floor.

The single floor of the upper level comprises a multifunctional space including a conference room, exhibition areas, and a restaurant.

The roof

The public had access to the roof until 2023 and could enjoy the belvedere and a terrace arranged around four interior courtyards: enclosed patios with their only opening pointing towards the sky.

You can get closer to the clouds by going up to the terrace at the top of the Grande Arche, which offers a 360° view of the Paris region.

The hypercube that was ultimately built is not quite the one that the idealistic architect, Johan Otto von Spreckelsen, had imagined.

His utopia was shattered by the harsh realities of real estate, not to mention some political misdeeds (not discussed in this article).

While the sky does indeed enter through some pores of the building, it lacks its most poetic part: two other “clouds” that were supposed to float on either side of the building, above landscaped gardens.

For further information, I invite you to browse the travelogue of Paul Andrieu or to watch the film “La Grande Arche,” released at the end of 2025.

Thierry Allard

French photographer, far and wide

Landmarks of historic Paris

The Louvre is 8 km from the Grande Arche, with a difference in elevation of 25 meters.

The Louvre pyramid (22 m) stacked on top of the two Triumphal Arches (15 and 50 m) on the Parisian axis would just fit into the vertical opening (90 m) of the Grande Arche.

An impossible axial photograph:

The Pavillon de l’Horloge, in the center of the Louvre, and the pyramid opposite it are not quite aligned with the axis that connects the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, the obelisk in Place de la Concorde, the top of the Champs-Élysées with the Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, and the Arche de la Défense.

Please respect the copyright and do not use any content from this article without first requesting it.

If you notice any errors or inaccuracies in this article, please let me know!

You may also be interested in other examples of Parisian architecture

3 thoughts on “ The Grande Arche in Paris, sky’s window ”